Without any inside info, I took a look, made some suggestions and asked some questions about ways to improve what Smartypants Vitamins is doing. I’m a fan of the brand and just wanted to put together a brief video of some thoughts on how they might be able to do things better.

Video and write-up, whichever you prefer.

Acquisition

Bridging Direct Response with Brand

I wanted to share a presentation I gave last week.

Most people feel that it’s an “either/or” thing when it comes to picking DR vs. brand. I’d argue that it’s an “and” thing.

Let me know what you think below.

The Overflow Effect – How My Client Doubled their Revenues from their Facebook Ads

Imagine a scenario where all you’re doing is running Facebook ads, let’s say a video ad in particular. And you’re not running much of any other media – no search, no affiliates, not up on Amazon. Whether you think you’re killing it or just can’t seem to crack the code, here’s something you need to know:

You may be giving up more than 50% of the sales you could (should) be generating.

Why? Because just like we experienced when I was overseeing TV media at Beachbody, there’s a spillover effect (sometimes massive) from platforms, especially ones using video, to, well, everywhere else. Consumers don’t all immediately purchase. Some go do research of their own on Google and Bing, others go looking for promo codes to see if they can find the best deal, and some just go to Amazon because they are loyalists.

Let me cut to the chase as simply and quickly as possible – if you’re running any sort of volume on Facebook (video or otherwise) or on YouTube or on TV, you have to, have to, have to run, at the very least, the following:

- Paid search ads on Google and Bing for your brand terms & trademark terms, including misspellings of both, as well as any buzz phrases or USP’s you include in the marketing (think, P90X’s “Get ripped in 90 days”)

Too many people underestimate Bing. Sure it’s much smaller than Google, but it’s still bigger than zero, takes very little to manage it, and usually has a very high ROI.

And if you don’t those revenues or margin, do you mind if I take them? Didn’t think so. All those little’s will add up. That’s how you win.

- Affiliate channels – whether you’re set up thru networks like Commission Junction, LinkShare or otherwise, get going with your affiliate program. Especially if you have a physical product, do as much as possible to get connected with the top affiliate networks – they’re the ones who can and do drive more than 70% of the traffic – Ebates, ShopAtHome, RetailMeNot, Offers.com, Savings.com, etc.

- Amazon – I’ll keep saying this until I’m blue in the face. if you have a physical product, you need to be up on Amazon. Assuming you want to make more money. Yes, absolutely, it’ll cannibalize some of your sales. But a very small percentage of them, so little relative to the incremental revenues you’ll get that you won’t stress about it. There are a ton of folks out there who are Amazon buyers only. And correct, you don’t own the customer. But would you rather have fewer sales or more sales?

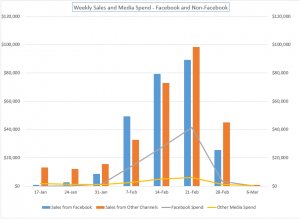

To illustrate the ripple (sometimes called a “halo” effect, which frankly I can’t stand), let me show you some stats from a campaign I managed for a client.

We scaled from $100 a day to $12K per day in 2+ weeks on Facebook, drove 17 million video views, 30,000 shares, 10,000 comments and 125,000 total engagements. In 8 weeks, we generated over $500K of revenue on roughly $190K of media spend, which for this campaign was better than goal. The only reason we pushed like this was because we saw the ROI. (As you look at the chart below, the reason for the precipitous decline is that we ran out of inventory – yes, a major bummer. But we are finally back up and seeing similar performance numbers, after a huge break.)

Here’s what I think is particularly notable in this graph: at the peak, Facebook represented 80%+ of the media dollars spent for this product (the blue line), but less than 50% of the revenues generated from the campaign, when measuring last (or really even first) click attribution. The blue column is Facebook-attributed revenues vs. the organ column which are revenues attributed to another channel.

Put another way, we spent the vast majority of the media dollars on Facebook, but got the majority of the orders through non-Facebook channels. So had we not been on Google, Bing, and set up with affiliates, we would have given up more than half our revenues. In this case, we actually didn’t own the product on Amazon, and that represented another 20% of revenues.

I’m a big believer of appropriately attributing orders back to trackable media, but in this case, because we knew what the baseline was prior to the Facebook media blasting off, it was very clear that the lift in Google, Bing and affiliate traffic was the direct result of the Facebook media. Had we not looked holistically at all media and revenues sources, we would have also miscalculated the real value of that Facebook media.

Frankly, I’m amazed more people aren’t talking about this effect. I’ve mentioned this at a few events I’ve spoken at in the past couple months, and I’ve literally seen people leave the room afterwards to tell their traffic folks to make sure any gaps they had are plugged.

Whether you’ve dismissed or ignored these older channels, at the least, get the basics in places. (I’m not talking about long-tail non brand terms. I’m talking about keywords like your brand. Very targeted, highly qualified traffic.)

And like I said earlier, if you don’t want the margin dollars from Bing (or anywhere else for that matter), give me a ring. But something tells me you want to keep all of it. So make sure your campaigns are set up to do so.

If you have additional insights you’d like to share, I’d love to hear them below.

Don’t make these two mistakes when doing competitive research

Learning and modelling off of your competitors is something everyone should be doing.

Whether you are new to a field or a long-time player, anyone can benefit from seeing what others are doing, if only to spur some new ideas.

(Note, modelling and learning is different than flat-out plagiarism. There’s a fine line between “not reinventing the wheel” and copying word-for-word. Don’t be afraid to use others as a model, but just bring your own creativity or persona to it.)

For purposes of this article, I’m going to assume the business is a digital marketer, but the lessons apply everywhere.

What most people do when they conduct competitive research is that they go through someone else’s funnel in the same way that they assume a “normal” buyer would. They want to see what the buying experience is. And so they go and buy the product or service.

Totally makes sense and is logical. You’ll see some of the steps, see what types of offers they are making, and what the experience is of receiving the product or service.

But if that is all you are doing – essentially buying once from a competitor, the first time around – you’re missing out on additional valuable information.

In particular, here are 2 items to add:

- Don’t buy.

At least not right away.

It sounds really simple, but go thru the sales process, but don’t actually buy anything. In doing so, and this is assuming the marketer is at least halfway decent, you’ll start to see retargeting ads all over the web. Pay attention to what they look like, where they appear, what types of messaging and offers they include.

Also, again assuming the marketer has some level of sophistication, they will have a different set of emails that they send to buyers vs. non-buyers. And so by only buying, you miss out on all those non-buyer emails. Given that 95% of people who hit your site won’t convert, your ability to remarket to them is crucial. Most people only focus on banner / Facebook retargeting ads, but forget about email (on multiple levels). So go thru a competitor’s funnel and make sure you submit an email address. Then give it a week or two to see what you get hit with.

(Quick note, the easiest way to know which emails are for buyers and non-buyers is to use a feature in Gmail most people aren’t aware of. By simply adding “+” and whatever words you want, you essentially have an infinite number of email addresses to use, all hitting your inbox. For example, if your email is bob@gmail.com, then you can use bob+amazonbuyer@gmail.com and bob+amazonnonbuyer@gmail.com as your email addresses and those will all go to the same place. Then just set up a custom filter and custom label. The emails will end up with tags that will help you identify them quicker than seeing what the actual email address was as each email comes in).

By the way, this approach of not buying can easily be applied in the offline world. See what a sales rep does after you say no. How do they try to overcome objections? When do they call you back? Do they send emails. Clearly, there’s a lot more variability by sales rep in most companies, and it’s much costlier – both for you and for the other party – so much so that you may not want to do it. (Not to mention getting on someone’s list and receiving an email is much cheaper than having a sales rep call you back – I prefer not to do the latter, but you have to make your own decisions.)

My point is that research is research – it’s just the process and media that might be a bit different.

- Remember that the marketer might be testing something new.

Good marketers know that they need to be testing all the time. Unfortunately, you can’t know whether you’re in a test cell or in a control version of someone’s funnel. As such, you may be in an experience that they are testing out – buyer or non-buyer – and so need to keep a healthy sense of paranoia as you’re doing competitive research. You might even need to go thru it a couple times (as a buyer and non-buyer, depending on how good you think they are).

The reality is that you shouldn’t accept and immediately implement anyone’s funnel. You don’t know their business model inside and out. They may be optimizing for revenues, for breakeven, or for a metric that means nothing to you. Who knows? So that paranoia should be in place even if you knew for certain you were in a control experience. The point is to see some new things and then figure out how you might want to test for your business.

Neither one of these strategies is rocket science. Behave like a buyer as well as a non-buyer. You’re not looking for the info about a data set of 1. You’re looking for what the 100s and 1,000s of visitors to your site do. And then just be slightly paranoid because you be part of a test your competitor is running. Be thoughtful and careful about trusting that what you experience is actually working.

Just as you read books from folks you admire, to learn from the experience and wisdom, so too should you do what you can to learn from those around you in the marketplace.

What mistakes have you made or have you seen others make? Leave a comment below.

What’s Your “Unfair Advantage”?

A good friend who recently started a business is getting preferential treatment from her vendors. They have given her low minimum order quantities and generous payment terms on her orders. Both are typically reserved for customers with significant history and volume.

Frankly, it’s almost not fair that she gets these terms while others don’t.

To be clear, there is nothing happening that is remotely illegal. At the end of the day, these types of decisions a vendor makes are business decisions.

But there’s more to the story…

My friend has been working in the same industry as her startup for the past 10 years. Her business partner’s family business has even more years of experience in the industry.

They both have history. They both have relationships. And good ones at that.

And because they are using the same vendors as her partner’s family business, the startup is essentially piggy-backing on the trust built over time.

These two entrepreneurs knew this going in. And frankly, that’s a big part of why they decided to take the leap.

They knew that they had to manage their cash carefully. These two also knew that they had an advantage many others don’t. They didn’t have to buy as much as everyone else (less upfront risk), and they didn’t have to pay as quickly for what they did purchase (favorable payment terms).

But I’ll be honest.

I was kind of annoyed when I first heard this.

Very quickly, that annoyance turned to admiration and respect.

“Smoke ‘em if you’ve got ‘em.” Especially when not everyone has ‘em, right?

The reality is that anyone starting a new business should try to leverage their own unfair advantages as much as possible.

Some people know how to code.

Some know how to build websites.

Some have a ton of relationships.

Some are really good at sales.

Some are just really smart.

And some know they can outwork everyone else in their industry.

When you marry those unfair advantages with passion and competence, that’s when risk goes down and the chances of success dramatically increase.

In fact, risk management is a skill most entrepreneurs don’t get enough credit for. Most people view entrepreneurs as risk-takers. And certainly most entrepreneurs are more tolerant of risk than the average individual.

But very few people talk about how well entrepreneurs manage that risk.

Maybe they start small and build slowly.

Maybe their model has multiple ways of evolving such that if one path doesn’t work, there are other ways to go.

Maybe they start a business where they have a lot of history and relationships. Which in turn leads to decreasing the financial constraints on their business.

And then for some, it’s not maybe. It’s real. They manage their risk by knowing they have what many people would term an unfair advantage.

When in reality it’s knowing what you got and being smart about using it.

This isn’t to say that people can’t and haven’t had success in entirely new industries or roles.

But if you could dramatically reduce your risk and increase your chances of success, why wouldn’t you?

So what’s your unfair advantage and are you leveraging it to its max?

Please leave a comment below because I’d like to hear what you think.

You can also follow me on social media or connect with me directly by clicking the links to the left.

Customer LTV: The Single Model Your Business Success (or Not) Relies On

If your business includes the following: 1) get customers; 2) make a profit from those customers; then this post is for you. While I’m being a bit tongue-in-cheek, I’m not kidding all that much. Because there are some fundamentals about how you manage your business model that transcend all business types.

In my recent posts, I’ve made reference to understanding the value of a customer. I think it is the single most important piece of information you need to have to run your business. This applies regardless of what category you place yourself in – direct response, brand, or anything else. And in a lot of the work I do with folks, I raise it early in our conversations not simply because it’s neat and interesting to have, but because:

- If you are running any paid media, you need to know the value of a customer to know if the media you run is working – and what “working” actually means

- It helps to ensure you actually understand your business model. As a unit economics model, it has to capture what actually shows up on the P&L, and in so doing, you figure out how much you make per customer. That is a lot more important than most people think. If you’re not making money, on average, on an individual customer, then you’re not going to make it up on volume…

- With this model, you create a way to understand the key levers in your business, which, AND THIS IS THE MOST IMPORTANT PART, helps you to determine what ACTIONS you take. Having a model that does NOT result in action means there’s something wrong with the model or you’re not using it correctly.

So what the heck do we mean by the value of a customer (or “Customer LTV”). I’ve seen so many different definitions:

- The revenues generated on a customer’s first transaction

- All the revenues generated by a customer regardless of timing

- Gross revenues less refunds/returns over the life of a customer

- Net revenues less costs (with varying definitions both of what each of those means)

To be clear, NO DEFINITION IS RIGHT OR WRONG. But what is crucial is that whoever is using the information knows what it means and is using the information in an appropriate manner.

So let me jump in to what I consider Customer LTV:

- For a given media source, what contribution margin does the average customer generate.

- For example, when you run branded search, what’s the value of that customer? When you run Facebook ads, what’s the value of that customer?

How, then, do you calculate contribution margin?

First, calculate Pre-Media Margin by taking all the revenues generated by a customer over their lifetime, adjusting for returns/refunds, customer cancellations and credit card declines (“Net Revenues”) less all the variable costs that are the direct result of those revenues. These may include physical product costs, merchant processing charges, shipping, warehouse/fulfillment expenses, customer care, server costs, and bad debt.

Net Revenues Less Variable Expenses = Pre-Media Margin

Then, include a desired margin on your revenues (more on this in a moment). The difference between the Pre-Media Margin and Target Contribution Margin is the amount you can pay to acquire a customer and still hit your goal. Usually the term “allowable” or “target customer acquisition cost” means the goal, and then the actual figure (media divided by customers) is CPO or CPA (Cost per Order / Cost per Acquisition).

Pre-Media Margin Less Required Profit = Target Customer Acquisition Cost / Media Allowable

Thus: Contribution Margin = Net Revenues Less Variable Expenses Less The Cost of Acquiring a Customer

Notice that by working to understand the value of a customer, you have backed into how you can afford to pay to acquire that customer. Which in turns allows you to manage your media in a more explicit and intentional manner. You now will have a way of determining what it means for your media (marketing) to be “working” or “not working”.

This is a very simplified view of a customer lifetime value model (also called a margin model):

I like to break down the numbers into front-end (first transaction) and back-end (subsequent transactions), seen below. What time horizon you use for the subsequent transactions is a bit of a business decision, based on cash flow requirements, risk associated with those revenues, etc.

(Note: this structure is not a proprietary one. Most of the top direct-response marketers use a version of it. You can also see how the folks at Digital Marketer use it here. Or if you want to dig in really hard, this is a great book about how to use metrics in your business.)

In the below example, imagine a marketer who signs up a customer for a trial offer and then upsells them into a subscription or continuity offer – these are clearly NOT their numbers, but anyone familiar with Proactiv, the anti-acne product, might have a model structured in this way. The company may be subsidizing the first bottle knowing that customers will buy a bunch more in the future.

In reality, the media cost should actually be part of the front-end because the marketer pays for the media on day 1 but has to wait some time in the future for those future sales to come in.

Cash Flow Implications

Unless you’re one of those fortunate marketers who has a ton of cash in the bank, even if you knew with a high degree of confidence that customers will generate a good amount of revenues (read: cash) in the 90, 180, or 360 days after their first transaction with you, you have to be sensitive to cash flow. Which will affect how aggressive you can be on going in the hole with new customers or how aggressive you can be with scaling your media.

This decision is business-specific. If you have a physical product business, you may need to pay for inventory well before your continuity orders kick in (or you may have great terms or a short lead-time that allows you to not have to carry that much inventory until you actually need it).

This is where information / digital products have an advantage, since often times one of the only/biggest investments is the creation of the product/service. And then of course the media spend to acquire the customer.

Below is very simplistic example to showcase the point for a physical products business:

- Before even running media, this physical product marketer has already paid out $2,000 for inventory.

- They are running a low-priced trial offer so they may not cover their initial expenses even when they’ve acquired customers.

- Perhaps they don’t pay for media right away but pay weekly, and perhaps the warehouse gives them 30 days to pay for work they’ve done.

- At that point the first set of continuity orders ship out and generates revenues/cash for the marketer. If this were a multi-pay offer, then that push out cash even further.

This post isn’t meant to focus on cash flow but you can see the implications on cash when running media. And it’s something that you have to model. You need to understand your model, so that you can pay your bills, based on when customers will be paying you.

For whatever reason, the 90-day breakeven seems to be a standard that many people I talk with use, but again, that depends on your model.

Target Margin

In the lifetime value model above, I used a return on revenues of 15%. This is another business-specific decision. While it is somewhat arbitrary, there are a few factors you want to consider when setting it.

- What are your business goals? If your goal is about pure customer acquisition and you don’t have a high burn rate, you might be able to run at a low/zero margin.

- Who would do this? Plenty of VC-funded companies run at negative margin, or if your play is about building a list to monetize, that strategy might push you to run this way.

- What is actually possible? As I’ve mentioned, one of the values of this unit economics model is to understand your business model. You may find that your revenues and cost structure don’t support the margin you thought was attainable. Kinda important to know.

- Balancing volume with margin – higher margins are always nice but you have to balance that with volume.

- This point is much more nuanced and doesn’t have a good scientific explanation. All I know is that it’s true.

- For each form of media and each campaign, there seem to be breakpoints where if you have an allowable above a certain number, you can jump your media spend. So while you might want to increase your target margin (thereby lowering your allowable), it might mean that you are making it more difficult to run at scale. Someone should always be looking to see how much media they think you can run based on different allowables/margins.

A More Exhaustive Analysis

Let’s dig deeper and look a specific model, a physical product (in this case a supplement marketer).

Before jumping in, I need to make something clear – these models apply for each media channel. If you only have 1 channel or don’t have the info to separate out different customers, use what you have right now, but start building the tools and systems to track customers from different places.

The values used below are for an average customer. Meaning, if everyone takes your $5 initial offer and 15% of the people take your 1st upsell which is $100, then your average order value is $5 + 0.15*100 = $20. For the back-end, it’s the same thing – the simplest way to calc that figure is to take all the back-end revenues generated by customers (typically we group them into cohorts based on the timing of their first transaction) and divide by the number of customers.

In this below example, you can see I’ve expanded the model to include more line items that are relevant for this business model. Let’s go through each step by step:

- The marketer generates gross sales, but some customers call to cancel their order right away and some credit cards don’t get correct authorization.

- That leaves shipped revenues, revenues associated with orders/customers where an actual product shipped out.

- A certain percentage of customers want refunds – I’ve assumed 10% for both front and back-end when in reality it’s rarely the same. Nor is it the same for customers who are getting their 2nd bottle versus their 7th one. Long-time customers, not surprisingly, have much lower return rates than newer customers.

- That gets us to net revenues.

- At this point, we need to deduct all the costs associated with these orders/revenues – the physical product, fulfillment and warehouse fees (which many people include in their product cost), shipping expense (UPS, Fedex, USPS, etc.), credit card processing, customer service, and bad debt assuming this marketer allows people to pay in installments.

- We are now at pre-media margin. And in this case, the marketer wants a return of 15% on their revenues, which means that as long as this marketer spends $48 or less to acquire an average customer (reflected in this model), they’ll do so.

Each of these line items can have further nuance, for example:

- There are warehouse costs incurred when customers return product, not to mention the product returned may or may not be salvageable.

- Cancels on the front-end are likely different than on the back-end.

- But wherever you are, and whatever level of detail you have for your business, start there as your baseline and then work to improve the information you gather.

To my prior point that this model should drive action, in addition to helping manage media, this marketer might identify an opportunity with reducing shipping expense. Not that it is easy to do, but if this marketer could decrease the average shipping costs for the back-end from $16 to $13, that would add $3 to their media allowable. And as so many folks before me have said, “He/She who can pay the most to acquire a customer, wins!”

This is a fictitious model, but if it were real, I would work with the team to understand what opportunities they have both to increase revenues and to create efficiencies in the cost structure, serving both the media allowable here as well as the broader P&L.

Other Business Models

Info Products

What about marketers who aren’t selling a physical product but rather are selling an information product, like an online training program?

Well, the process is the same, but the specific line items would be different. If it’s a pure info product, then there would be no shipping or warehouse fees, nor physical product costs. Some of those might be replaced with the cost of delivering the product – whether an e-book, or server and bandwidth fees associated with a membership area.

Lead-Gen

The same structure of the model works for lead-gen folks who are not managing to paying customers but to leads (names on a list, email opt-ins, etc.). The only difference is that the Target Customer Acquisition Cost needs to be multiplied by the percent of leads who convert to paying customers. That gets you a Target Cost per Lead

What about fixed costs – why are those NOT included?

Noticeably missing from these models are fixed costs, such as labor, rent, technology, and even product development costs (R&D for a product, the cost of developing a training program, etc.). I’m often asked why I don’t include them in the model. There are a few reasons:

- The goal of the model – often referred to as a “Margin Model” – is to understand the marginal revenues and costs associated with new customers. As such, it is very rare that an average, additional customer creates additional fixed cost requirements for a company.

- As you scale the business, you will likely need more resources to support the growing customer base, but this model is capturing the economics at the unit level, not at a macro level.

- Put more simply, acquiring and servicing a single additional customer doesn’t drive you to hire another person.

- In addition, these fixed costs mentioned above are often sunk costs – whether you generate 5,000 customers, 100,000 customers or 3 customers, for at least a period of time, you are already burdened with those expenses or you have already incurred them.

- Now, you absolutely need to run some analysis and look at your full P&L to know how many customers do you need, assuming you hit your target CPA, to breakeven when you factor in fixed costs, G&A, etc. – this is crucial work that I am not under-emphasizing. My focus right now is on this unit economics / margin model exclusively.

Interestingly, I get asked whether or not to include headcount in this model but no one ever asks whether investments in technology (servers, software, etc.) should be included. My response, in addition to the point above, is that you should look at your people similar to technology – they are investments in your company’s future.

Is it wrong to include any of these fixed costs in the model? No. But I would say that you’ll be under-cutting your allowable, and especially as you look to scale, you’re going to be holding yourself back from pushing as aggressively as you might ordinarily.

If you can’t tell, I’m pretty passionate about this topic. But not simply because I come from a quant background, but because I believe strongly that it is one of the crucial components of running any business.

You need to have someone who owns your model(s). And then have people who work with those analysts to identify points of leverage in the business and specific tests to run to optimize your business. The ROI on this is a no-brainer. Not to mention it might save your business.

Please leave a comment below because I’d like to hear what you think.