Ed O’Keefe asked me to come speak at his event in Nashville this year. I’ve received his permission to share the video.

Acquisition

How Blue Apron Revealed a Lot More about Customer Acquisition and Retention than It Likely Intended To

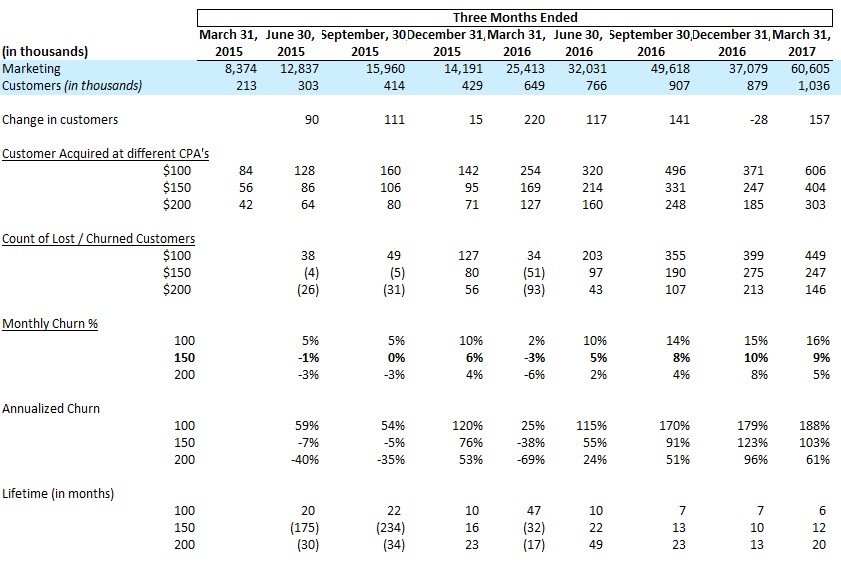

I’ll cut to the chase first. I have no inside information, but my analysis has lead me to conclude that Blue Apron is acquiring customers at a rough CPA of $150, its current monthly churn appears to be ~10%, and the Company eventually nets ~$150+ of contribution margin over the lifetime of an average customer.

Those numbers aren’t written in their S-1, but the analysis used to come up with them is based entirely on the information provided in that S-1. No one else, as far as I have found, has published them. I frankly haven’t seen even educated guesses at specific numbers. Other than saying that the current number is probably higher than the $94 figure they disclose in their filing – but that number is based on the average of 2014 through early 2017 results.

For background, I helped to build the analytics team at Beachbody, then ran media and customer acquisition there for the last 5 of my 8 years. I’ve since spent the last 2 years helping my clients use information to dramatically improve their customer acquisition and retention efforts. This isn’t an entirely new area for me. And certainly, if someone or the Company proves me wrong, I’ll be the first to acknowledge it.

My goal here is to show how you can dig through information that may not be explicitly detailed and how I got to my conclusions.

More important than what the numbers they shared reveal is what the implications are for their own business as well as others in the meal delivery space, and the broader subscription business. More on these points in a bit.

What Blue Apron Shared

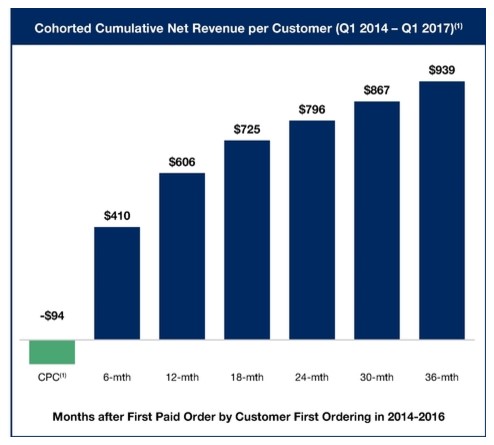

The below graphic is the one that has been making the rounds. It is pulled out of their S-1.

Chart #1

What the graphic shows is the average cost to acquire a customer during the 2014 to early 2017 period. I’m not sure why it’s called CPC (“Cost per Customer”), but it’s more normally called CPA (“Cost per Acquisition”). In addition, it shows the lifetime revenues for customer over various periods after their first paid order. Since the date range considered is 2014 to early 2017, but we are only in mid-2017, the metrics shown for 30 months out and beyond are based on customers in the earlier part of the range.

Let’s also not gloss over the clearly very intentional label, “Months after First Paid Order.” One frequently-used component of Blue Apron’s customer acquisition strategy has been to give away meals and/or the first box. That language is specific, such that if a customer doesn’t pay for the first box, they are excluded from the lifetime revenues part of the table.

As for the Marketing Expense associated with these free boxes, there’s this language from page 67 of the S-1 – “Also included in marketing expenses are the costs of orders through our customer referral program, in which certain existing customers may invite others to receive a complimentary meal delivery…The cost of the customer referral program is based on our costs incurred for fulfilling a complimentary meal delivery, including product and fulfillment costs.”

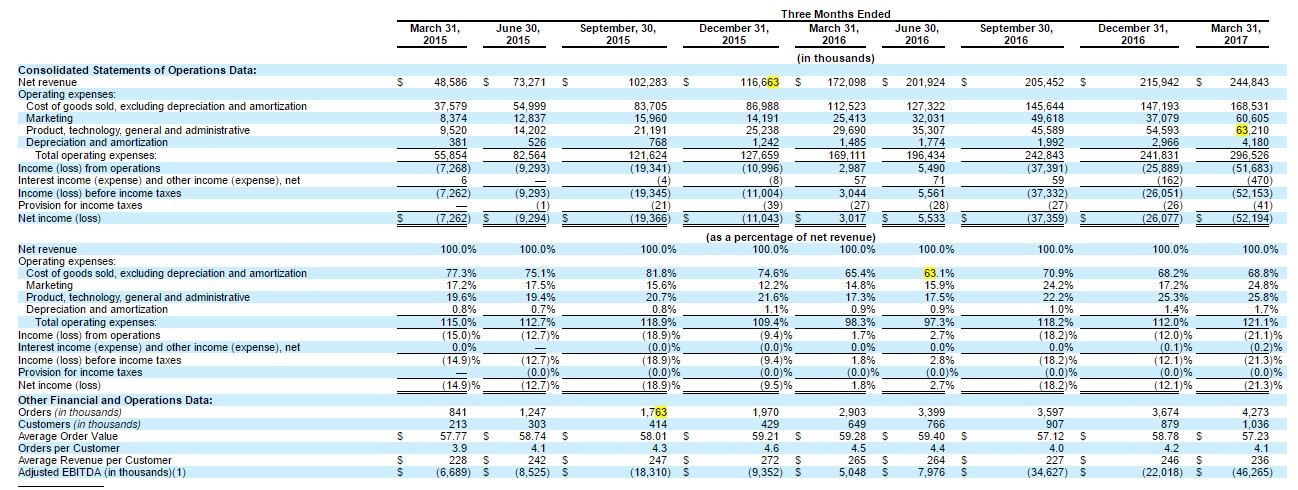

Next, the below is another table they presented. It’s an eye-sore for everyone, but has some valuable information in it.

Chart #2

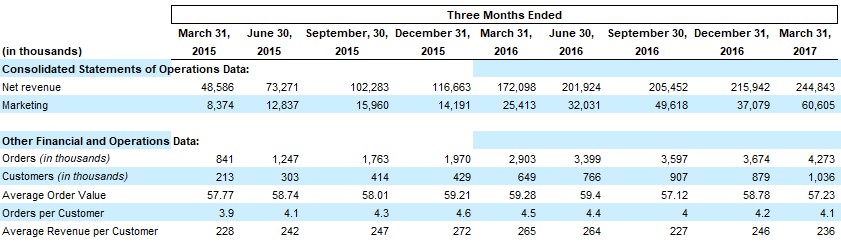

Here is a view of the more telling parts of this table.

Chart #3

Based on Charts 1 and 3, we have the information to calculate their acquisition cost and churn.

I’ll start with churn:

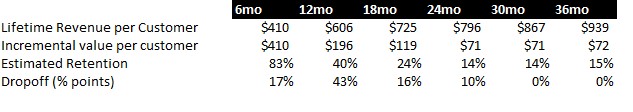

The first line is provided in Chart #1. The second line is just the difference from one period to the next. Now, the estimated retention is based on the following:

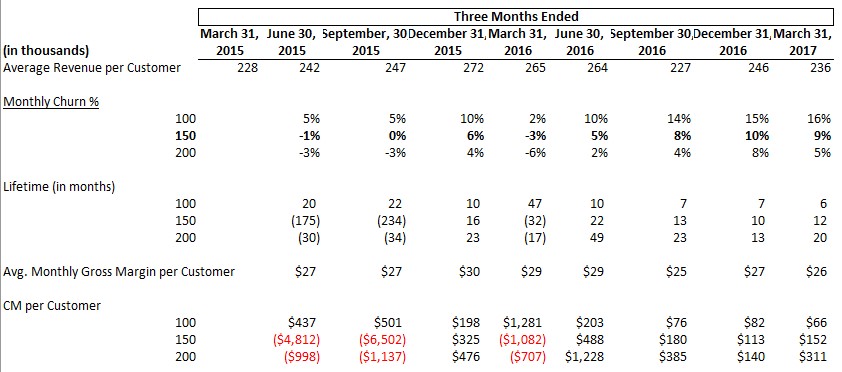

- From Chart #3, it looks like the Average Revenue per Customer is roughly $247 per quarter. I’ve had to make some simplifying assumptions – this number is a simple average – not perfect but likely close enough.

- $247 per quarter implies $494 per 6 month period. So if in the period from 6 months to 12 months in, customers generated an incremental $196 of revenue, then that implies that Blue Apron only has 40% of them left ($196/$494). This is the calculation behind the 40% figure in the 12mo column. The same math is used for the rest of that line.

- Dropoff – this is the percentage point difference from the prior period – Note that I haven’t shown Day 0, which was the starting point, to calc the 17% for the 6mo column.

- A couple things jump out, whether from the Estimated Retention Line or the Dropoff one.

- Somewhere between month 6 and 12 is where the 50% figure is crossed, which helps to give a sense of the average stick rate of customers

- Estimated retention seems to go up from month 30 to 36. My guess is 2 main factors are causing this: a) we don’t have the exact same cohorts in the analysis, only what was available when the S-1 was put together, so it’s not pure apples-to-apples; and b) I’ve made simplifying assumptions based on Average Revenue per Customer, but I would guess that those customers who have stuck around 30 and 36 months have higher-than-average quarterly revenue.

To get a bit closer to when the 50% threshold is crossed to give a sense of the average retention rate (at this volume, I think it’s fair to say that the mean and median are approximately the same), we can do some additional analysis.

Using a straight-line average of dropoff – use the figures at 6 and 12 months as the starting and ending points, respectively, we can generate this table:

From there, it looks like somewhere around month 10.5 is when the 50% figure would be crossed. If the average customer sticks around 10.5 months, that implies monthly churn of roughly 100/10.5 = 9.5%.

This figure is going to be supported as I get into the CPA calculation. But one other way to back into that churn rate is to take the Company’s reported $939 of lifetime revenue, and divide it by the simple average revenue per customer, which I’ve calculated at $247 (per quarter). That implies 3.8 quarters that a customer sticks around, or 11.4 months.

The simple average of these two calc’s would be 10.5 months. I’m discounting a bit for scale to get to my 10% figured.

Couple additional points here – the average lifetime revenue from those cohorts in the 36mo column will go up. They’ve simply reported the data they have now. So arguably LTV will only get better, but at the same time, as the Company attracts a broader group of customers, that’ll be counter-balanced with lower-quality customers. We can argue about what retention plans they have in place, do people get stickier to the service, etc., but for now, let’s assume this is all a wash.

Now, to calculating the actual CPA Blue Apron is running at

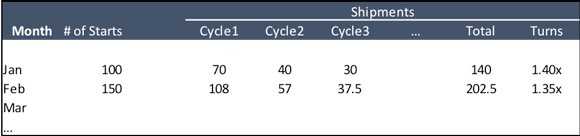

The top part of this table is from Chart #3, the rest is the analysis based on it – my explanation of the table is below:

Change in customers is simple math – the net change in customers from the end of the prior period to the end of the current period.

The next section – Customers acquired at different CPA’s – shows the number of customers acquired based on the Marketing spend reported by the Company and based on varying CPA’s. Since the average from 2014 through early 2017 is $94, I’ve made the assumption that the Company CPA has been increasing over time – not unreasonable at their scale. I’ve just used simple $50 increments after trying out a few different ranges.

For example, for Q1-2017, based on $60MM of Marketing spend, and at a $150 CPA, that would imply 404K customers who joined during Q1.

Based on these figures and the net change in customers (to repeat, a calculated figure based on the table), the Churn section is then created. At $150 CPA, that would imply the Company lost over 247K customers during Q1-2017.

Monthly churn is based on the average of the prior and current period figures, adjusted for the fact that those numbers are quarterly. Again, sticking with the Q1-2017 and $150 CPA figures, that would imply churn of ~9%. I’ve simply multiplied the monthly figures by 12 to show annualized numbers. Anything over 100% describes a scenario where the Company is essentially turning over its entire customer base each year. We know that in actuality that isn’t the case – there are clearly some customers who have stayed on for a very long time, but it’s a helpful way to make sense of those over 100% figures.

Finally, Lifetime in monthly is calculated based on the Churn percentages – the opposite of what I did in the original churn analysis.

Which assumption on CPA is correct?

If we assume a lower figure, that means that churn is higher. And vice versa.

But if we layer on the first analysis here, and use the “starting point” of ~10% churn as a possible figure, that leads us to look at the $150 CPA line. Note that during Q4 of 2015 and 2016, the Company lost a lot of customers, which isn’t unexpected given the holiday season. Even with the Q1-2016 figure, as much as CPA doesn’t stay constant, the 10% churn figure and $150 CPA seem like defensible metrics for the business based on the information they provided.

Many folks have commented on the fact that Blue Apron didn’t explicitly reveal its churn. But I wanted to share that it’s possible to back in to that figure.

As for the $150 CPA, it seems reasonably that the current CPA is ~50% higher than the average over the past few years. At their volume, that isn’t unexpected, not to mention, they are going after more mainstream customers, as opposed to the early adopters. That usually means spending more to reach those folks. Finally, competition has increased – everyone like pure competitors such as Hello Fresh and Plated, as well as additional options like Munchery, Uber Eats and even Door Dash – have no doubt made customer acquisition more costly for Blue Apron.

What this really means for the business, and how much does the Company make on each customer:

Using the average revenue per customer, alongside the disclosed cost of goods, the Company makes roughly a 33% Gross Margin on its revenues (Revenues less Cost of goods, which include product and fulfillment expenses). Adjusting the quarterly revenue per customer to a monthly basis, the average monthly gross margin per customer is ~$26. (Note, at a $150 CPA, that implies 6 months to breakeven on a customer, which is exclusive of all of the Company’s additional expenses such as G&A, capital expenditures, etc.) If we then multiply that margin figure by the average lifetime, we get a lifetime gross margin, which when reduced by the acquisition cost, gives a lifetime contribution margin (“CM”) per customer. At a $150 CPA, the Company is roughly making $152 per customer.

Implications for Other Businesses

For starters, Blue Apron has significant funding – almost $200 million according to Crunchbase. That has allowed the Company to operate at a significant loss for pretty much the entirety of its existence. Many of the other larger food delivery companies are in a similar situation, though the vast majority of companies at large don’t. In addition, operating in the red on a per customer basis for 6 months+ is more taxing than most companies can afford.

It’s also tough to run a business when 10% of your customer based is cancelling each month. Those are figures reminiscent of my days at Napster in 2006, when the iPod was the hot thing and subscription music was widely criticized as a non-starter. (This was also the period when Blockbuster came out with its competitive product to Netflix, and everyone “knew” that was the end of Netflix. I think we’ve all seen how that worked out.)

10% monthly churn is really high. As I mentioned earlier, that equates to turning over your customer base more than once a year. Which puts dramatically more pressure on customer acquisition. And while the company only has tapped 2-3 million total customers (I’m again making some simplifying assumptions), which is 1% of the US population, with rising competition, it makes its model more difficult. Not that I’m betting against them necessarily. More just looking at what their metrics seem to indicate.

Net net, this is a tough business. The margins aren’t great, customer acquisition isn’t cheap, and retention is unlikely to jump from 10 month to 20 months in the near future.

Something would need to change for their model to dramatically improve. With these dynamics, it’s not just a “we’ll make it up on volume” play. But to the extent one or more of those components – core margin, acquisition cost, or retention – could change markedly, the model could be different.

The only one of these metrics that was likely reasonably understood early on was margin. Until they (or anyone else) began testing, acquisition costs and stick rate were really unknowns.

Which go to the larger point for other businesses, whether in the same or other categories, and that is about how to get as quick an understanding about the business fundamentals and dynamics as possible.

To be clear, there are plenty of subscription businesses that are thriving, both in the food category and beyond. This is absolutely not a criticism on the category – and frankly it’s not a criticism as much as it is a deep analysis on the Blue Apron business itself.

Every business has to manage through the relationship of Customer LTV and Customer Acquisition Costs. And then must layer on constraints such as cash, risk it is willing to take, and business objectives – in determining the better path to proceed down and what strategic decision it wants to make as it evolves.

That is the challenge and the fun of forging ground in new categories.

I, for one, am certainly very interested to continue to watch Blue Apron along its own path.

What I Learned from Managing $500MM+ in Media and Acquiring over 10MM Customers

I’ve talked to a number of people recently who think that optimizing and scaling campaigns has this magical and mystical aura around it. And that there’s some secret to doing so.

Well, I’ll let you in on the secret…

During my time as the SVP, Media & Customer Acquisition at Beachbody, we ran over $500MM in media and acquired more than 10 million customers. I now work with a variety of direct response marketers — helping them to optimize and scale their businesses, identifying not only gaps and opportunities, but also key points of leverage to exploit.

And whether at Beachbody or with my clients, I’ve found that just like everything else, there is no magic.

Instead there is a process to follow, primarily driven by a list of questions, to help identify gaps and opportunities in your business. (Because oftentimes, those gaps and opportunities are where optimization and scale happens.)

Some questions have quantitative answers, others are qualitative. Some questions identify gaps in…

- information (oftentimes reports that should be run regularly)

- a marketing issue (why you don’t offer installment billing, for example)

- or a training issue (do your customer service reps know how to respond to certain customer issues)

Almost always, the first answer someone gives is not the entire story, and so pressing on additional questions can help to uncover the next layer of understanding. Those questions are harder to script because they are dependent on the specific answer and/or individual responding.

Today I’m sharing the 6 category process I use to dig in to a business, regardless of whether it’s doing $10K a month or $100MM per month. The process is the same, it’s just at a different scale and level of complexity.

But it’s not for the faint of heart.

Most likely, some of what you’ll find from this process, you can take immediate action on, like training. Other areas require testing. (Where possible, PLEASE test before you change a control.)

But before you go out and implement anything, there’s one crucial step to take…

Prioritization.

Everyone is resource-constrained — for people, time, dollars, or traffic. We would all love to test everything we think of, but of course we can’t. And not all tests are created equal. This is where doing a bit of math can help you to understand the possible impact of different tests. You’ll likely have to make some assumptions but even with reasonable guesses, you’ll realize how little (or how much) a certain test could move the needle, when compared to others.

Here’s an example:

You may believe that both your landing page and one of your later upsells could use some improvement. Based on some assumptions and running some numbers, you might find that if you could increase the front-end conversion rate from 3% to 3.1%, that change would have the same impact as tripling your conversion rate on the upsells from 1% to 3%.

But with some business context, you might also know that the upsell is a hard sell at this point – maybe it’s really expensive or maybe the offer just isn’t compelling as it needs to be. Not to mention, a later upsell requires more traffic to get the test to statistical significance. As such, that little bit of math you do might help you move forward with the front-end test instead of some lengthy upsell one.

Too many people miss this prioritization step and as a result, don’t focus on the key points of leverage in their business.

So… ready for the 6 category process? We’re about to get into it. But first a word to the wise…

The below is fairly in-depth and so it might serve to identify where you ASPIRE to be. You may not have these things in place now or in a year. Don’t be intimidated. If you’re at the beginning of your journey, pick one or two of these gaps and close them. When your business is young, even the smallest changes can have a tremendous impact.

If you have a mature business but are looking to take it to the next level, you’ll want to address more of these gaps or hire someone to get it done.

Ready? Let’s go.

6 Revenue-Focused Categories

The list below is by no means perfect, nor comprehensive across all businesses.

But it does reflect the primary steps in my process of helping to break down a business to find areas to maximize.

The core questions fall into 6 categories that are primarily revenue-focused. They may also help to define roles and teams as the organization grows. I’m a huge believer in managing expenses, but if you’re a younger, growing company and you don’t have sales, the rest doesn’t matter:

- Traffic / Media

- Conversion

- Offers

- Non-converting leads

- Post-Transaction

- Retention

Let’s start with…

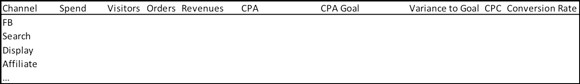

1. Traffic / Media

Start with your traffic sources.

Do you have a weekly report showing…

- traffic

- spend

- conversions

- CPA

- conversion rate

- AOV (Average Order Value)

…by traffic source (SEO, Facebook, Email, etc.)? Can you analyze trends weekly? If not, you’ll likely find that simply reporting on this type of information will provide a foundation upon which to build.

Then you can starting digging in with a number of questions:

- Do you know customer LTV by channel?Because performance relative to goal is the only way you can say that one channel is doing better than another. (I’m assuming you’re a direct-response marketer and not simply focused on impressions and reach.)

- If the LTV is different, are you actually managing to different CPA goals?

- Are those different goals on your reporting spreadsheet and are you managing to those different goals?

- What channels are performing better than others?

- What sub-channels, ad groups, etc. have shown success and which have struggled?This sounds like the same question, but the former is at the channel level. This is about looking at results where everything happens — in the details.

- And then, there’s the simple question of when was the last time you tested new copy or images?

Not all questions will come from a report. For example:

- How repeatable and scalable is an opportunity or channel you’re considering? You might get pitched what you think is a great idea, but if it’s only a 1-off and you can’t replicate it and scale it, you might want to consider passing. For example, someone with a list offers you a JV deal, but you need to do a ton of customization on your site and to your backend to run it. And that customization isn’t applicable to other JV partners. That takes work and is a potential distraction to your team who might be able to focus on other opportunities that are repeatable and scalable. This is not to say you never do 1-off’s, but rather that you look at these types of opportunities with a discerning and intentional eye.

In general, in my experience, the companies that have had the greatest success know that repeatability and scalability are two keys to their success. And those companies know…

The one big mistake to avoid.

And this applies beyond media. Once you find success with a channel (or offer), go deep and hard on it. It’s really easy to get so caught up in testing different sources that you fail to fully exploit one (or two) that is working. Or like a lot of marketers, you might have shiny object syndrome or get captivated by something you hear from a friend.

If you look at the successful marketers out there, they aren’t actually masters of every channel. They are usually really good at one or two. When you think about it, that’s not surprising. They probably tested a few things, found some success and then pushed hard there. Because they knew that they couldn’t be great at everything but also that they needed to go deep where they were having success.

Sometimes that’s the difference between those who scale and those who don’t. Two companies might both achieve early success but it’s what they do with that success that can separate them.

Key Takeaways

- Work to understand the value of customers from different channels and that you’re managing to those respective goals.

- Filter on repeatable and scalable opportunities.

- Once you find success, exploit the heck out of it.

Next up…

2. Conversion

Most people have the raw basics down:

- Click through rate

- Overall conversion rate

- Average order value

Then you can starting digging 1, 2, or even 3 levels deeper with a number of questions:

- Do you know conversion rate by traffic channel?

- If you have a 2-step conversion path (landing page -> checkout page->thank you page), do you know the click through rate from landing page to checkout page and from checkout page to thank you page? It might reveal something to you, such as break points in your funnel. Translate this to other parts of your funnel and your business.

- Can you betterunderstand the different steps in your business? For example, do you track how many people submit an email address or a credit card on your form but don’t complete an order? This might tell you something about your form, page, offer, or something else.

- What is the take rate for each upsell in your funnel? Do you know it overall and by channel?

- When you calculate AOV, are you including continuities initiated from that first transaction when you consider Lifetime Value? Meaning, when you analyze initial orders, are you appropriately valuing them(while understanding there are cash flow implications to consider)?

I know… I just hit you with a ton of questions. Take a deep breath.

Then, just pick one of them and focus. Or, hand that list to whoever handles conversions and allow them to pick. I’m intentionally throwing a bunch out there to give you different ways of looking at your conversion path.

Then, there’s the most underused and valuable conversion tool that digital marketers fail to add to their mix:

…a phone number.

But isn’t the phone old-school technology? Yes, it is. But you also might not realize that many marketers make 25% or more on a phone order than an order online (even factoring in the cost of talk time and agent costs), not to mention conversion rates can be dramatically higher on the phone.

So if a customer has a question or wants to order on the phone, do you let them? Particularly if you have customers 45+ years old or have a higher ticket offer?

Even if the idea of managing a call center scares you, you can do a simple 3-step test:

- Get a new prepaid mobile phone number for your business

- Put that phone number on the landing page AND checkout page

- You or one of your team can answer calls – even if you only want to answer calls 5 hours a day, put a voicemail message for when you don’t answer.

You will quickly figure out if people want to call, then you can see for yourself if the added work of more numbers, agents, or even a sales call center (VERY different than your customer care agents) is worth it.

Key Takeaways

Whether you’re sending your traffic to a…

- landing page

- phone number

- webinar

- Amazon

- physical store

…try to break down and track the process each step of the way.

At the least, you’ll have a baseline to measure from.

Better yet, once you break things down at a more granular level, you’ll uncover opportunities you hadn’t seen before.

3. Offers

There is plenty of info out there Tripwires, writing copy, etc., so I’ll focus on a couple other areas that can have a significant impact on your business.

Upsells

Anything less than 2 and you’re probably leaving money on the table.

Giving customers the ability to order more than 1 of whatever you offer — 2 or 5 or 10 of something — is an upsell. They don’t have to be some magical new product. While ingestibles have had real success offering multiple units, if you offer a training program, why not suggest that a customer buys a second for a friend, or gets a second for a discount?

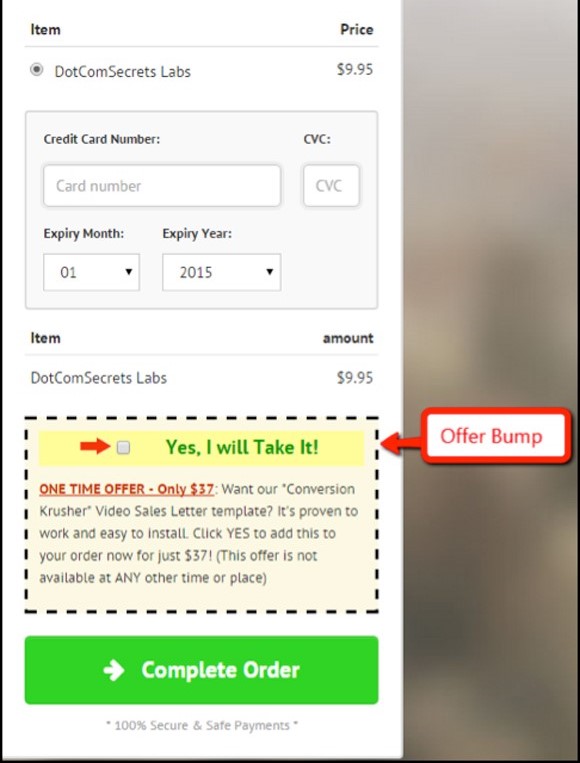

Offer Bumps

Russell Brunson has a really slick version in Step 2 of his process here.

Don’t have another product to sell? Be an affiliate to a relevant and complementary product…

- If you are in weight loss, go partner with a company like HealthyOut or a food delivery company

- If you’re in the dating niche, find someone who can help your clients with personal style and attire

- If you teach internet marketing skills, find a technology partner (look at what Digital Marketer has done with InfusionSoft)

Then, when you test, you can see what your traffic responds to, and that might give you some insight into what product your audience will respond to.

Installment Billing and Payment Plans

Some marketers offer a premium for installment billing — the multi-pay total is actually more than the 1-pay.

(By the way, this is also called financing and what each of us did when we bought a car or a house.)

Some marketers (see: infomercials) start with a multi-pay offer and then offer an incentive for 1-pay (managing to bad debt and getting cash on day 1 can be hugely valuable).

Neither is right or wrong. Or inherently good or bad. But are you doing either?

Price Testing

When was the last time you tested increasing or decreasing your price point?

You can test by traffic or adding/removing something simple in the offer in case you’re worried about customer backlash — test to a small percentage of your traffic, but you need to get at least 500-1000 orders to feel good about the results.

Key Takeaways

What can you do to generate more?

When all else fails, go check out what your competitors are doing!

4. Non-converting Leads

The average conversion rate to most sites is ~5%. That means 95% of visitors aren’t converting.

Which means it’s absolutely necessary to be using retargeting. Are you?

On Facebook?

Here’s what a retargeting ad looks like on Facebook…

Display?

Via email for cart abandoners?

Test when and how many to send – perhaps start with 3 emails – 20 mins post-exit, 23 hours later, and then 1 week later.

You can dig in to your retargeting efforts with these questions…

- When was the last time you tested your creative on retargeting?

- What can you apply from your retargeting campaigns to cold traffic.For example, lookalike audiences on Facebook or Google?

- If you have a higher price point product (over $500 for example),have you tested calling non-converting leads? (There are some specific legal rules on calling people, so take a look at the rules before doing so.)

- When was the last time you had someone go through your site to make sure that pixels are actually in all the places you thought they were? Or whether your remarketing automation is actually working as you believe it to be?

Key Takeaways

Don’t let anyone go.

Even junk traffic can be monetized — I know a guy making a killing by taking people who mis-dial toll-free numbers and offering them a survey which has been funded by a research company. Don’t harass people, but even people who inadvertently raised their hand can be valuable.

Regardless, definitely make sure you have a path for people who don’t convert.

5. Post-Transaction

Again, there is a lot out there about offering more on the thank you page.

So let’s target other areas of your business

Do you send an order confirmation email?

Do you offer content or additional offers in that confirmation email?

What about a shipping confirmation email?

Do you provide onboarding content?

Here are some great examples for SaaS businesses, but applicable to any business.

This one frankly could come pre-transaction but do you make it super easy to get going with something as obvious as a “Start Here” button

Do you tell your customers what to expect when using your product?

- If you offer a cleanse, do you tell customers to be prepared to be cranky on day 3 or 4, so that they might want to start on a Thursday so their work doesn’t suffer?

- If you sell them an ingestible, like a shake, do you provide recipes and/or make suggestions on how to make it a part of their daily routine?

- Do customers know to expect that muscle soreness doesn’t usually kick on the next day but 2 days after (because of DOMSS – Delayed Onset of Muscular Stiffness and Soreness)

- On day 30, if they purchased an ingestible like protein powder, do you send them an email with a quick reorder link?

Is it easy for people to find answers to questions or know where to go or do you try to make it nearly impossible for customers to contact you?

And in that case — are questions responded to in a timely manner?

Key Takeaways

Most of these suggestions don’t immediately impact your bottom line. But if you can take steps to make sure that people’s experience of your product or service is great, and that they feel like you are looking out for them, they will like you that much better.

And their chances of success with your product will be higher.

Which means repeat and referral business. (This is the cheapest source of traffic you can get.)

6. Retention

Note: This section is applicable both to continuity offers (e.g. membership sites, subscriptions, etc) and “1-time” transactions

Let’s start with a few questions here:

- Especially if you have a continuity or subscription-based business, do you have a single person accountable for retention?If the answer is everybody or nobody, that may be the first place to start.

Well beyond retention, having a single person accountable for a component of the business increases the chances of it improving, or the rate by which it improves. And simply because there’s a single person accountable doesn’t of course mean that individual is the only one working on it. It merely means that they are the owner who then coordinates with other folks on the team.

That individual could then focus on understanding and improving questions like the following:

- How long do customers stay on continuity? By channel or offer?

- Are you breaking down customers into cohorts based on start month to see if there are any changes over time?

- Do you know your refund rate? Remember that refunds are a part of customer retention, even if you don’t have a continuity product.

- What are the top 3 reasons people cancel or return your product/service?

- What do your customer service reps say when a customer wants a refund? Based on any kind of segmentation?

The above gets you to a baseline level of understanding. Again, don’t get too caught up if you don’t have this historically – at the least, beginning the process of tracking sets you up going forward. The next step is to see what you are actively doing to extend the lifetime of a customer.

- Can the messaging on the front-end be tweaked, without killing conversion?

- What content should be communicated to the customer after they have purchased? (Overlaps with the post-transaction section above.)

- Can you partner with someone to offer a product or service that addresses the bigger challenges people face?

One of my friends has a product to help people build their own business, but he knows that one of the biggest challenges his customers face is psychological, not technical. So he has partnered with a personal development coach offering his services to his customers as an upsell. He can also test offering these services, potentially for free, given how high his price point is, to customers wanting a refund.

“Before you cancel, can I connect you with a personal development coach who will spend 45 minutes with you to help get you over the barriers that have been holding you back?”

That’s a pretty compelling message.

- Can you keep people on a downgraded plan when they want to cancel?

When I tried to cancel my ClickFunnels account, which was $97 / month, I got an offer for $19 /month (I think) to keep pages but they aren’t live. But if I cancelled, my pages were deleted forever. So I’m paying to pause my account.

That’s pretty slick!

Here’s a question I’m sure more than a few of you are asking right about now:

What if you don’t have a subscription model?

(Other than the snarky, “well you should get into one…”)

Retention doesn’t have to be about continuity billings but can be about making sure someone is active and/or happy enough to buy when you put out new offers.

Ultimately, what can you do to create happy and successful customers? It sounds so obvious, and yet too often we fail to dig in to understand our customers’ key pain points – just spend a couple hours taking customer care calls and you’ll hear it first-hand. Then figure out how to take that knowledge to tweak your customer’s experience.

Key Takeaways

No matter what, your business shouldn’t be just about traffic and acquisition.

As everyone knows, it’s a lot easier to sell to an existing customer than to a new one. So what can you do to nurture your existing ones?

So here we are…

This process really is about identifying and digging in to the key components of your business. Whether you’re a 1-person shop or have teams all over the place, the actual process of going through and answering these questions – at least for the first time – will likely identify gaps as well as needs (oftentimes information needs).

But the process doesn’t stop after that first time. It should build to be a continual process that eventually gets parsed out to team members who have accountability for improving their respective areas.

Final note: everyone is resource-constrained, so you’ll want to find the biggest points of leverage in your business. But don’t shy away from small wins. Remember, a lotta littles can add up. When you and your team start paying attention to the more granular details in your business, that is when you will create true optimization and scale.

So at the very least, pick a single area to focus on. Make it something achievable. And go make it happen!

I’d love to hear your thoughts on where you have challenges driving growth and where you’ve had particular success.

(This post originally appeared on the DigitalMarketer blog.)

The Most Important and Powerful Model for All (Direct Response) Marketers

If you’re running paid media of any sort (Facebook, TV, affiliates, direct mail, or otherwise), you have to understand one thing above everything else: the value of a customer. It is crucial to help you manage media. The lesser-considered discussed but equally important benefit of having a customer LTV model is that it helps to identify key points of leverage in your business and where to direct resources for testing and optimizing.

In this video, I walk through the customer LTV model (aka, the margin model or the unit economics model). Regardless of your understanding and use of the model, my goal is that you will learn something new and approach it in at least a slightly different way than before.

As always, please let me know if you have any questions or comments.

How Lessons from TV Helped to Scale a Facebook Video Ad Campaign

Watch this case study where I show how the lessons learned from managing DR spots on TV helped us to best exploit and scale a Facebook Video Ad campaign. I break down how we scaled a Facebook Video Ad campaign from $100/day to $12k/day in 3 weeks.

Based on my experience running over a half a billion dollars in media, we knew where to be and what to look for to capture the demand we generated from spending profitably into 20 million views! It also turns out that Facebook Video Ads have a lot more in common with Infomercials than you might think.

Serving the Underserved Creates THEIR Experience

In a literal way, inclusivity is the opposite of exclusivity. And so, while being exclusive means something is for a select group, inclusivity, particularly for marketers, doesn’t necessarily have to about trying to include everyone. At times, companies can simply target people who have been underserved. Especially when we think about one of the big no-no’s in marketing – that of trying to be all things to all people – it’s important to understand this distinction and not make the presumption that inclusivity is going against that adage. The below examples demonstrate how engaging and enrolling audiences that have been ignored, in a sense crafting a great experience for the underserved, can yield great results.

Sephora: Clueless Shoppers are Welcome

Plenty of industries are filled with employees who like to make sure (potential) customers know just how “knowledgeable” the employee is, often at the expense of the customer. For my part, I grew up a cycling fan and wouldn’t have enough time to list off the number of times I felt so belittled because an employee in a cycling store was seemingly offended by what he considered an offensively-simple question.

The beauty industry has a similar dynamic.

For its part, the beauty brand Sephora has done an exceptionally good job of making the beauty-shopping experience actually feel inclusive, not snobbish. Blogger Alicia Jessop has described Sephora as the equivalent to women of what a hardware store is for many men[1]. Just as men often go into hardware stores and browse without having any specific product in mind, women often shop at Sephora with that similar sense of discovery, exploration, and accessibility.

It’s fair to say that most everyone has gone into a store where there was a certain product domain they knew nothing about, then either tried to portray they knew something they didn’t, or they didn’t want to acknowledge that they knew nothing. Unless we are just plain lucky, it’s a rare occasion that we leave with the right product and certainly none the wiser.

One of the primary reasons we as consumers behave this way is an expectation of how the “expert”, in this case a store employee, is going to respond. Prior experience has led many of us to be intimidated in environments where there is a lot of domain expertise or technical skill.

But Sephora, while obviously not perfect, mitigates this effect in several ways.

The most obvious way is the store layout. Unlike department stores where all the merchandise is behind a counter and only accessible by employees, Sephora has put product front and center, so that customers can touch and try products without having to ask anyone. There is no gatekeeper to get past or to ask what might be an ignorant question. Instead, customers have free reign to products at Sephora – to touch, hold, and try at their leisure. This may seem like a minor detail, but given the department store dominance in beauty and just the fact that a customer doesn’t have to speak to someone to try something that grabs their attention – these have been big changes in the beauty industry.

Next, when customers do need help, Sephora staff are there to serve them. Training is an important aspect of Sephora’s employee onboarding, whether on the customer service side or the technical side (how to help a customer select makeup that suits them as well as applying it). Training is done at the store level but also through Sephora University, the center for the company’s training. While creating its own training center, aka the University, is an advantage that a massive company like Sephora can afford to do, putting attention to how employees treat customers is something that any business can do, whether big or small.

It’s important to acknowledge that no business is remotely perfect. In researching Sephora, there were plenty of examples I heard about sub-par, off-brand experiences. Particularly in retail, where the inherently imperfect human interaction drives a good part of the experience, perfection isn’t the goal. Being a ton better than everyone else is. On a consistent basis. At the same time, setting up aspects of the business, such as the store’s design, that are not dependent on how an employee chooses to behave, can shift that burden and reinforce the bigger experience that is trying to be delivered.

As we all know, a company’s brand isn’t simply created from one component of the business. It is built everywhere. And in Sephora’s case, creating a welcoming, interactive and fun environment, whether through the store design or its employees’ attitudes, has been a key to their success. It affects customers in the store, their likelihood of making a purchase, and certainly the stories they tell (primarily positive in Sephora’s case), which drives the chances they return and/or how they influence others to do so.

Gwynnie Bee: Serving Plus-Sized Women

When the apparel and accessories business Stitch Fix launched, they initially didn’t target plus-size women (anywhere from size 10-14 and up, depending on whose arbitrary definition you want to choose from). It was a business decision that Stitch Fix (a former client of mine) made, amongst others that also included not serving men or kids, all of which they do now.

This isn’t about right or wrong for Stitch Fix, but their success and focus on its core group of customers, meant that there were opportunities for others to target those that weren’t being served. Stitch Fix was not the only subscription business focused on delivering these same products to women, but in being one of the earliest and certainly the largest (most recently topping $1 billion in revenues and 2+ million active clients), who they were and were not serving was much more visible.

So as Stitch Fix was building its business, and to a certain extent educating the broader market on what they offered, Gwynnie Bee launched at a similar time, exclusively serving plus-sized women. Not that Stitch Fix played into the stereotypes that are all-too-often found in beauty magazines, but the fact that they didn’t stock apparel for plus-size women gave Gwynnie Bee the opportunity to highlight how it was differentiated from the category leader in Stitch Fix. Gwynnie Bee was specifically offering clothes for a group that are not always served by apparel retailers. To this day, beauty magazines constantly reinforce the idea that skinny is better. To its credit, Gwynnie Bee embraced its target customer, and didn’t try to show size 2 women on its site.

Body image is admittedly a sensitive topic; and yet from a practical side, the reality is that many women in the US fall under the plus-sized definition. So while Gwynnie Bee was targeting an underserved and perhaps niche category, theirs was by no means a group with small numbers.

(It’s interesting to note that Stitch Fix eventually did serve plus-size women, in addition to men and children. And Gwynnie Bee announced in early 2018 that to be considered truly inclusive, they were not remaining exclusive to plus-sized women.)

There are plenty of other examples on servicing what isn’t considered mainstream; certain shops target “big and tall” men, some restaurants are “family friendly,” while others are clearly designed for couples.

In all of these cases, whether Sephora, Gwynnie Bee, or others, inclusivity isn’t about trying to be everything to everyone. It’s about targeting a particular group of people, especially those who may be underserved. And then making them feel warm, understood, and served in the manner which we’d all want to be treated.

[1] Jessop, Alicia. “What’s Good Wednesday: Why Women Love Sephora.” https://aliciajessop.com/2012/08/22/whats-good-wednesday-why-women-like-sephora/ August 22, 2012.