You may have decent metrics in place. When people ask you what a customer is worth, you confidently say a figure.

You may even have a quick response for what the average stick rate for a customer is – “7 months,” you might utter.

“We lose about 30% in the first month, 20% of those remaining in month 2”, and so on.

Just knowing these metrics is a lot more than most folks. (See here https://goo.gl/Pln3vU for my post about Customer LTV if you want a better understanding).

But let me ask this question – do you know what percent of those who dropped out did so proactively? Because the answer is NOT 100%.

In fact, depending on your business, it could range from 60% to 95%. Which is a MONSTROUS range. Said a different way, 5% to 40% of those people who dropped off as paying customers didn’t take a proactive step to do so.

Which begs the question, “What happened to them?”

One of the primary reasons that customers who didn’t want to cancel got cancelled was that their credit card didn’t process.

Yup. That annoying part of the business. The one you can never get a straight answer about. The one whose fees range from 2% of revenues into the double digits depending on your business’ risk profile. Because remember, it’s not just processing fees; it’s chargebacks, refunds, and a bunch of other little line items that add up.

Merchant processing is the bane of many a marketer’s existence. Sure, there are more partner options than ever before – Paypal, Stripe, Amazon, not to mention the “traditional” folks like auth.net, Vantiv, EasyPay, and so on.

(A small point of clarification before we get too far – subscription is the same thing as continuity, auto-ship, auto-renewal, or any other label where customers are billed on a recurring basis. I’m just using the term “subscription” for simplicity here.)

Insufficient funds, wrong expiration date, and reported lost card are some of the top reasons why credit cards decline on recurring billings. Oftentimes, these customers would like to continue being customers. But unless you are a utility or Amazon or Netflix (I’d argue that those latter two might now be considered the former), customers can be lazy, forgetful, or just too busy in taking steps to make sure their subscription stays active.

The next question is, what are you, as the marketer, doing about it?

Let’s get some grounding first.

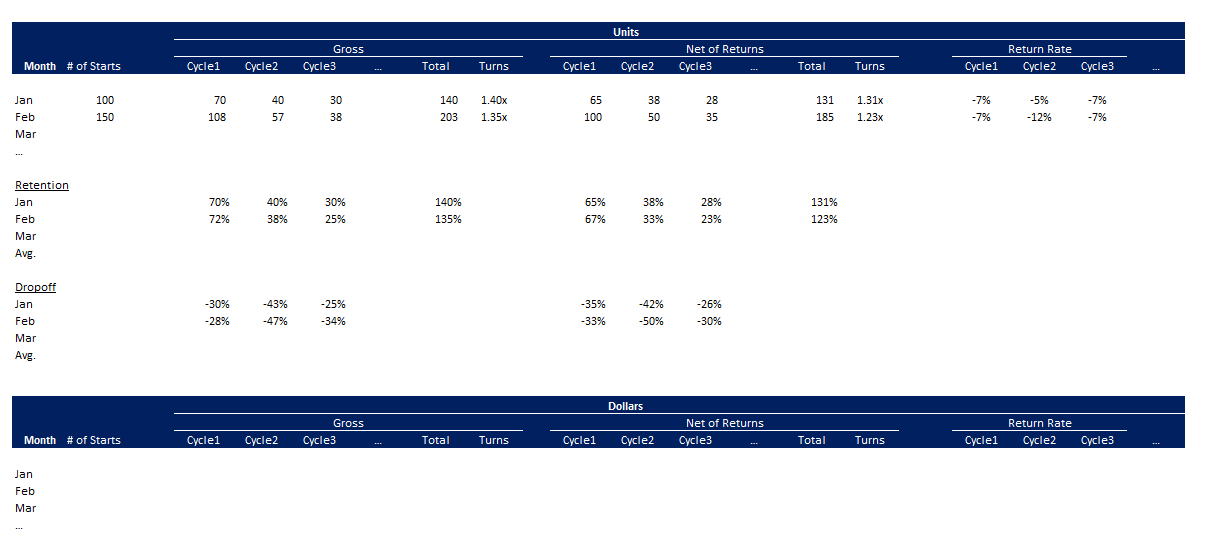

If you’ve got some sort of subscription business, hopefully you have a version of the report below – where you are tracking customers by cohort. In the below table, it’s by month, but it could also be by traffic channel, offer, etc. And really the goal is to measure how long people stick around at each rebilling period.

Notice that the report is broken down by cycle (which is the frequency you bill – monthly, quarterly, annually, etc.); by gross vs. net (of returns); and by units vs. dollars in the top and bottom sections. Each of these sections have value, and it’s important to look at your metrics in a couple different ways.

One of the ultimate goals is to know for every person who begins, how many total billings do you get from them. In the above case, this might be a free trial offer that rolls into a paid subscription. We want to track how many people bill in Cycle 1, 2, etc., and then roll that up to what I refer to as “Turns”. Obviously, we lose people each month. Tracking those people and laying out as in the table above, helps us to see exactly how many.

For the month of January, there’s a value of 1.4x in the Gross section. Which means that for every person who starts their subscription, on average, we bill them 1.4 times. And then because of returns, we net out at 1.31 times.

How far you carry out this analysis out depends on a few factors – how much info you actually have (# of cohorts and over what period of time), the risk you can tolerate when there’s a good amount of revenue generated in later months (and clearly later months is subjective based on your business and risk).

You can see that there are then calc’s on the percent of people who are still around (simply how many people billed relative to the # of starts) – this is labelled as “Retention,” again both calc’ed for net and gross. The “Dropoff” section is what it sounds like – what percent of the people who were still around dropped off for the next cycle.

Whether you have a lot of volume or a small amount, if you’re running a version of a subscription model, this is a crucial bit of analyses to have. To begin with, you need to know your numbers and this is one of the best ways I know of to understand what’s happening, at least from a purely quantitative side. It can provide a sense of how long people are sticking around, when more people are dropping off, what types of refunds people are asking for, etc.

Depending on how you allow/ask people to cancel, you should try to marry this data alongside “reasons for cancelling”. The info won’t be perfect – call center agents may make mistakes or customers may not click on the right button, but you should get some directional info on why people are cancelling. The most common reasons are things like, “too expensive”, “not using it”, “found something better”, “don’t have the time,” etc. Now, if you start to see a whole lot of “your product stinks”, “it doesn’t work as you described”, etc., then there might be something you need to address with the marketing, the product, the onboarding, or something else.

Once you have all this info, then it’s a matter of figuring out if something’s broken and where the key levers in the business are. That analysis leads to action (translation: testing) or fixing something that might be broken (don’t worry, you’re not the only one who has things break…).

The Part Many People Miss

So, you may have the raw reporting and analytics in place and you might have the reasons for why people cancel, but do you know how many people intentionally cancelled versus how many people actually dropped off?

These are “Unintended Cancels.” People who did not take a specific action to cancel, but you are no longer billing them.

So, what to do here?

Some ecommerce systems might provide you reporting on credit card processing issues, but assuming yours doesn’t, it’s time for some forensics.

The first place I’d start is with your merchant account, which, depending on the size of your org, might mean you need to pull in help from accounting or finance. Or it might mean you need to dig out that login info and do it yourself. Obviously, different merchant processing platforms have different levels of reporting. And how easy or not it is to know which declined orders are for your continuity, you try to dig in to see what is happening. You might have SKU-level info in there or you might have to use price point, for example.

All this to say, get to the bottom of what’s happening with your credit card declines.

What are the reason codes associated with those declines?

And then what are you doing about it?

Which should then lead to a combination of both a retry process as well as a dunning process.

The Retry Process

This could be manual or automated. But the point is that you are trying to charge a credit card where you received an error code. I get tired of saying this, but different platforms have different levels of reporting. Ideally, you’re only retrying those cards where you have a chance of success. For example, if you received an error code associated with a lost or reportedly fraudulent card, you have a 0% chance of success. It makes no sense to retry that card.

The vast majority of decline reasons are associated with insufficient funds. Whether it’s a $9.99 charge or $999 charge, a lot of customers’ cards decline for insufficient funds (which is why 1-pay or annual contracts have value – but I digress). There are a host of other reasons: expired credit card (more below), need to call the bank for some reason, etc.

The strategy you employ to retry cards depends on multiple factors, such as the fee you pay to attempt a charge, the margin your business nets on a success transaction, and your tech/merchant processor’s tech capabilities. You may want to retry the card every week for 4 weeks, you might want to retry on Fridays, which is payday for many people. Or you might have another strategy that you test into.

Here’s a link to a great write-up of an automated retry process – https://docs.recurly.com/docs/dunning-management – note that recurly is a vendor that I’ve heard some folks work with. I don’t have first-hand experience. But at the least, the info in that article is helpful and can provide a sense of the different ways you can approach the retry process and how you can use segmentation to try different strategies.

(I also want to make something very clear – as with all things, if your marketing is deceptive or if your product truly stinks, any strategy can be used for “evil” purposes. But I’m assuming your customers like your service, they know what they are getting, etc. – and the fact that they don’t reach out to fix a declined card can be as much the busy-ness we are all a part of as opposed to their not wanting the product. That’s why I have no problem describing these methods. I believe in integrity and ethics. And believe that if customers want to cancel, you should allow them to do so without jumping through massive hoops.)

Presumably, you’ll test a few different strategies, do the math on costs vs. the additional margin (not simply revenues) you make, and find something that works. Even if you can’t figure out an automated way when you first start this process, find a way to do it manually. Remember, these are customers that you’ve paid for who have stopped billing. These are real margin dollars.

By the way, you can also communicate with the customer directly. Which leads to the next section.

Dunning Process

This is basically another way of saying, “reach out to your customers proactively to fix the situation.”

The tactics you use to do so can include email, phone calls, FB messenger, or whatever other ways you have approval to reach out to people. Let them know their card has declined and that access to your product or service is going to end unless they fix it. Whether they can fix it online or they need to call a customer service rep, it’s always best to give people options so they can choose the way they’d prefer. It goes without saying but particularly when it comes to credit card info, it’s always important to stress that you know and follow the rules on how you collect and store credit card information.

Test and do the math to figure out what works (translation: where you are ROI positive).

Account Updater

I referenced expiration date issues above. And Account Updater is something I’ve discussed previously and falls under the retry process, whether automated or manual, above. The short version is that some banks provide a paid service to update the expiration date of a valid card but one that has simply gone past its expiration date. It’s an extremely rare customer that will call to update their expiration date. The beauty of the service is that you only pay per successfully-changed card. You send the info for cards that have this expiration date issue to get the date updated. Depending on your partner and your status, you can get charged anywhere from $0.06 to $0.18 per updated credit card. Now, no matter your price point, that shouldn’t be that hard to ROI.

There are only certain banks that participate in this service, so it won’t be 100% of the expired cards, but this can add meaningful dollars to your bottom line. You should reach out to your merchant processor or gateway provider to discuss how to implement this.

In Closing

Business can be tough enough as is. But when you have paid for customers that you lose for an annoying reason like their credit card not processing, it’s that much more difficult.

Go get that margin. And keep those customers.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.