In this video below, I spoke with Sklyar Ganz from The Farmer’s Dog, on how they could build out an affiliate program internally.

It’s a model I’ve seen and/or implemented multiple times quite successfully. As much as I’ve seen agencies help, I’ve seen particular success when the affiliate program is built internally.

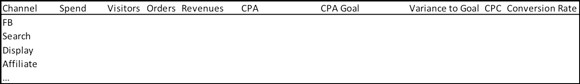

I walk through the playbook of how to do so, the roles needed (whether one or more people), the types of affiliates to reach out to, payout structures, etc.

I also make mention of a few tools. I’m listing those below.

- Finding partners – I’ve had a few folks speak very highly of this tool – Mediarails

- SEM compliance – Brandverity – for monitoring bidding on TM terms, etc.

- Leads/sales fraud – Fraudlogix – didn’t really capture much. Internal controls can work well here – to the extent you see sudden changes – traffic, CVR, etc. – that’s usually one of the better ways. If so, I’d def suggest doing so in excel/sheets – someplace that you can easily do the comparisons and then use conditional formatting etc. to call out big changes – much easier than trying to eyeball it manually.

- Email address verification – I can’t find the names right now. But there are a couple that I’ve used. Good to have in general even beyond the affiliate program. I’ll try to update this with some recommended vendors. (Certainly if you have trusted partners, pls let me know.)

Hope the video and the tools above help.

-Babak